We built a multiplayer, web-based Mario-like game with PlayroomKit... in 7 days!

How we transformed an open-source single-player game to multiplayer.

To play the game, open this link on a laptop or TV: https://cast-app.vercel.app/

Update: We've now proudly open-sourced this project!

Repository: https://github.com/grayhatdevelopers/platformer.ai

“The best articles are the ones with clickbaity titles.” - Unknown

We’ve been grinding our gears for 2 years at Grayhat, trying to get into games. Sure, we love web development and making the best products for our clients. Sure, we’ve built things in low-level vanilla JavaScript (at that point I would’ve loved me some chocolate JS) which haunt me in my sleep every night. But that doesn’t beat the fun in games, does it?

We tried everything; Unity. Unreal. ThreeJS (we even tried building a game engine in ThreeJS - more on that later).

The toughest part? Multiplayer. Every single time. Sure, we got some good, choppy single player working. But when it came to having more people join the fun, the logic just didn’t scale.

This year, we made a resolution to try something new. We brushed off the trusty ol’ game engine, Phaser3, and explored some interesting new tech for multiplayer - PlayroomKit.

(I mean, we’re not biased towards it. There are a lot of great solutions out there - it’s just that this is the one we helped build.)

It’s not really something new unless we give ourselves an insane challenge, is it? So here goes…

A multiplayer Mario-like game in 7 days.

7.

Multiplayer.

Day 1 - Inception:

“We’ll have to start by building a Mario-like game.”

“Last I heard, my job title wasn’t ‘Wheel Inventor’. Let’s try something else...”

We usually build upon the shoulders of giants, and this time was no different. We found some cool code for Mario in Phaser3 on GitHub. The code comments were in Chinese, so it took some translation with ChatGPT to understand what it meant.

We studied the refreshingly-nice documentation for PlayroomKit. Given that our objective was a classic platformer game, the Phaser example gave us a good high-level overview of how the game would work.

PlayroomKit's Stream Mode makes your game act like a typical game console - A separate screen plays the game, while the phone(s) are simply controllers. We found that was a nice option for our Mario game, since the classic feel of the NES is really hard to replicate on a phone’s tiny 5” screen.

Day 2 - Masters of Puppets

We ran the project, and fell into the classic dilemma. As a software engineer, it feels easier to rebuild a project from scratch because it makes the code feel more like you. That keeps you safe and comfortable.

I feel like the sign of a good software engineer is their ability to play with the cards they get and make the best out of it. I think of it as iterative rebuilding - use the right practices going forward, and refactor things which get in your way. Sort of like a long antibiotics course.

In our case, the code structure was great - but to actually have the player move whenever the controller on PlayroomKit was moved, we thought we might have to dive deep into the game logic.

Fortunately for us, we had a short brainfart - We could simply simulate keypresses within the game. I knew for a fact that game engines had such options, to account for bot players, and for automated testing. I’d seen a similar concept being used in Google’s own blogs, where they simulated keypresses on Chrome’s Dino Game. So we created a basic Phaser KeySimulator, and hooked it up with our phone controller:

// Simulate pressing a key

simulateKeyPress(keyCode) {

const keyObj = this.input.keyboard.addKey(keyCode)

keyObj.isDown = true

keyObj.timeDown = this.time.now

keyObj.isUp = false

keyObj.timeUp = 0

this.input.keyboard.emit('keydown')

}

// Simulate releasing a key

simulateKeyRelease(keyCode) {

const keyObj = this.input.keyboard.addKey(keyCode)

keyObj.isDown = false

keyObj.timeDown = 0

keyObj.isUp = true

keyObj.timeUp = this.time.now

this.input.keyboard.emit('keyup')

}

// An example of simulating the UP key for 1 second

simulateKeyPress(Phaser.Input.Keyboard.KeyCodes.UP)

setTimeout(() => simulateKeyRelease(Phaser.Input.Keyboard.KeyCodes.UP, 1000)That was it. No need to change controls deep down - We just puppeteered it from the top!

Day 3 - Powering Up

We whipped up a simple SNES controller using some great code from Codepen. We hooked the buttons with PlayroomKit’s state logic and started sending “inputs” from the controller to the cast screen.

See the Pen SNES Controller by Tim Pietrusky (@TimPietrusky) on CodePen.

So far, we’d gotten single-player to work. Game running on laptop, controller running on phone.

Some problems:

1. It was only single-player.

2. We had no way to automate testing. We had to play the game every single time to test every feature.

Day 4 - Luigi:

Our idea was to have a free-for-all of players filling the game, to test the limits of the PlayroomKit SDK. The original game’s code didn’t agree - it was built solely for a single player.

Hardcoding:

The first step to a good experiment is dummy data - you can’t tightly couple yourself in long implementations unless you know what you’re doing. In our case, it meant adding a second hardcoded player. After some blood, sweat and tears, and adding comments wherever we broke stuff, we were able to add a second, albeit quite diseased, player to the game, and make it perform actions based on a second player (also hardcoded).

Day 5 - Multiplayer Mayhem:

If it works for 2, it should work for 20.

We took a dive and replaced the hardcoded second player with some more generic logic which allowed an “array” of players to exist simultaneously, each with its own logic.

This took multiple breaks of the code and a lot of overtime, but the results? Worth it.

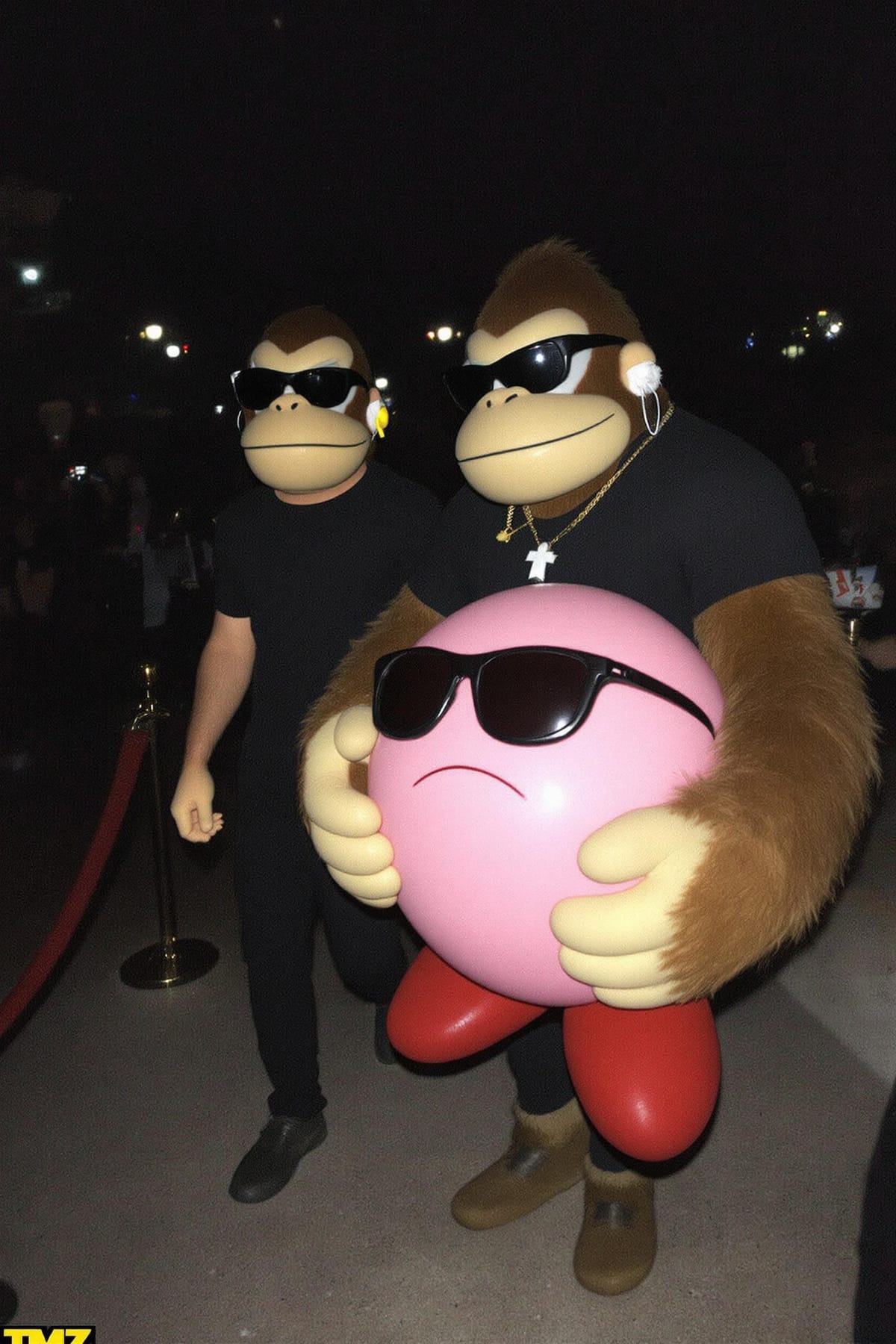

Day 6 - Field Test:

It was time to put the guinea pigs up to the test.

The chaos which ensued was exactly what we were looking for.

Day 7 - Deployment

We decided we’d had enough of juggling two repositories - one for the cast screen in Phaser3, the other for the controller in React - so we built a Turbo monorepo to make things easier to deploy, manage and test. Installation was pretty straightforward - until we got the genius idea to standardise Node versions across the two projects. There went our day.

Vercel’s got great support for Turborepo, so deployment was a breeze.

A noob's overview

Making games multiplayer has always been a hassle, and it's a huge barrier-to-entry for emerging game devs and studios.

For Grayhat, PlayroomKit was the key for a rag-tag group of web developers to explore game dev at warp speeds - no need to worry about infra anymore, we could now focus on making games look appealing and engaging.

That's the whole point. Apps can survive bad UI/UX to a certain extent. Games can't. If your game isn't fun, no one is going to even consider it twice. But that kind of craft takes time, and when you're spending hours figuring out why your networking code is sending corrupt data, you're either gonna spend big bucks, or a lot of hours. We have neither.

Sure, PlayroomKit has its pitfalls - there's a huge roadmap ahead with tonnes of work to be done. But I understand that it's early stage tech and there's a lot of potential in it. The Playroom team already has a huge list of amazing features, like built-in lobbies and joysticks, and we love being part of the journey. I'd put it as simply as:

It's the Firebase of game development.

Parting words 🚀

Have you tried game dev? What are the challenges you've faced? Would you like to read more about stuff like this?

DROP A COMMENT!

Disclaimer: We do not own the rights over any characters or any resemblance of the characters depicted in the game. This experiment was purely for fun and to learn, and we do not have any commercial benefit from it.